Hamilton Township Animal Shelter came under fire recently for its high kill rate and alleged violations of state law after the town poured money into its animal shelter. Despite spending over $1 million on this project and increasing its animal shelter operating budget by 56% since 2014, the shelter still killed huge numbers of animals. In 2017, the shelter’s kill rates for dogs and cats were 22% and 38%, but as many as 28% of dogs and 60% of cats may have lost their lives if animals listed in “Other” outcomes died. Furthermore, local shelter reform activist, Steve Clegg, uncovered shelter documents that suggesting the shelter illegally killed owner surrendered animals before seven days and did not have an adequate disease control program. As a result, the Hamilton Township Council announced it would investigate the animal shelter.

Recently, Hamilton Mayor Yaede and Health Officer Jeff Plunkett pushed back hard against the allegations. Mayor Yade issued a press release stating a shelter employee filed a “Notice of Claim” against several council members for allegedly creating a “Hostile work environment.” In addition, the press release cited several shelter insiders, including its veterinarian, who vouched for the shelter management. During a Hamilton Township Council meeting about the shelter, Health Officer, Jeff Plunkett, aggressively confronted critics and boldly claimed he could refute all the assertions against the shelter.

On July 16, 2018, the day before the Hamilton Township Council meeting about the shelter, the New Jersey Department of Health inspected the Hamilton Township Animal Shelter. You can read the full inspection report here. What did the New Jersey Department of Health find? Were Hamilton officials defending the shelter right or were shelter reform advocates?

Shelter Illegally Kills Animals Before Seven Days

State health department inspectors found Hamilton Township Animal Shelter killing “many animals” before seven days passed. Remarkably, the shelter killed not just owner surrendered animals, but strays as well, before seven days went by. Given the basic function of even the most regressive shelters is to allow owners to reclaim their lost pets, this is simply unforgivable.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.10 (a) 1. and N.J.S.A. 4:19-15.16 Many animals were being euthanized before being held the required 7 days after intake or impoundment. Records showed that numerous stray and surrendered animals that were received at the facility by animal control officers and other individuals were being euthanized within the mandatory 7 day holding period. Stray impounded animals are required to be held at least 7 days to provide an opportunity for owners to reclaim their lost pets. Animals were also being accepted for elective euthanasia and were being euthanized on intake. In the case of an owner surrender, the facility is required to offer the animal for adoption for at least 7 days before euthanizing it or may transfer the animal to an animal rescue organization facility or a foster home prior to offering it for adoption if such transfer is determined to be in the best interest of the animal by the shelter or pound.

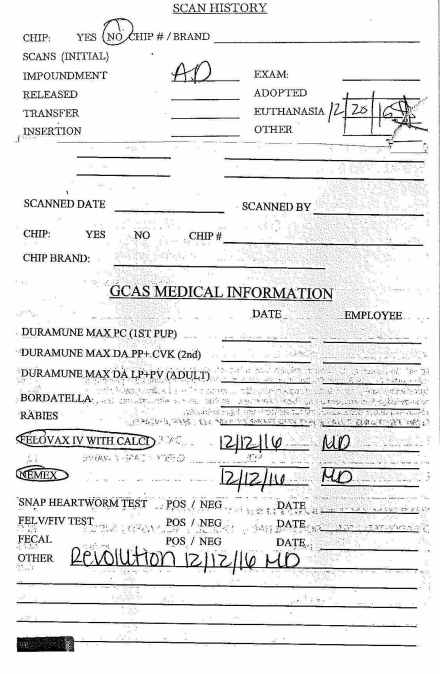

Animals Not Scanned for Microchips

Hamilton Township Animal Shelter failed to scan animals for microchips before animals were killed or released from the facility. Therefore, the shelter could have killed, adopted out, or transferred animals who already had families.

N.J.S.A. 4:19-15.32 Animals were said to have been scanned for a microchip on intake, but animals were not scanned again prior to release of any cat or dog for adoption, transfer to another facility or foster home, or euthanasia of the cat or dog. All impounded animals are required to be scanned for a microchip three times: upon capture by the animal control officer; upon intake to the facility; and before release or euthanasia. N.J.S.A. 4:19-15.32 Animals were said to have been scanned for a microchip on intake, but animals were not scanned again prior to release of any cat or dog for adoption, transfer to another facility or foster home, or euthanasia of the cat or dog. All impounded animals are required to be scanned for a microchip three times: upon capture by the animal control officer; upon intake to the facility; and before release or euthanasia.

Animals’ Safety Put at Risk

The shelter left a kitten in a so-called isolation room without proper ventilation. So how did the geniuses at the Hamilton Township Animal Shelter try to solve this problem? They opened a window so 90 degree outside air could flow in. In other words, the shelter left a kitten in conditions that could possibly cause heat stroke or at best make the kitten feel very uncomfortable.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.4 (c) The isolation room where one kitten was housed was not adequately ventilated to provide for the health and comfort of this animal at the time of this inspection. Inspectors were told that the window to this room was opened to assist in ventilating the room, but the outside air temperature was over 90 degrees and the auxiliary ventilation (HVAC) was insufficient to remove the hot, stale air from the room.

Hamilton Township Animal Shelter stacked wire crates used for housing dogs on top of each other and were at risk of collapsing.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.6 (a) Wire crates that were used to house dogs in the room where the ferret was located were stacked one on top of the other without proper support brackets creating a risk of collapsing. The wire crates used in this room were the type that are manufactured for temporary household use and are not structurally sound for use as permanent primary enclosures.

Despite spending over $1 million on a facility renovation, both the indoor and outdoor dog enclosures had peeling paint which dogs could ingest and be injured from. Furthermore, these surfaces could not dry quickly. So what was the stellar shelter staff’s solution to this problem? Leaving dogs outdoors for extended periods of time even when weather conditions were not safe for the animals.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.6 (a) The surfaces of the indoor and outdoor dog enclosures in the older section of the facility had peeling paint which could cause injury to the animals if swallowed. The surfaces of these enclosures were not impervious to moisture and easily dried, therefore animals were said to be left outdoors for extended periods of time in all weather conditions while waiting for these surfaces to dry.

If that was not bad enough, the shelter exposed cats to harsh chemicals (see below) when it cleaned the shelter’s cat enclosures. The cat enclosures had no doors between the feeding and litter box sections. Hamilton Township Animal Shelter’s bright staff put towels in place of these doors when they cleaned each section of the cat enclosures. Of course, the towels were unable to block the cleaning solutions that the shelter employees would inevitably spray on the cats.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.8 (a) The cat enclosures located in the new section of the facility have walls with portals between the main section of the enclosure and the feeding station and litter section. A significant aspect of these portals is to limit cross contamination that can occur when a cat is removed from the enclosure during the cleaning process and placed in an enclosure previously inhabited by another. These enclosures were missing the portal doors that separate the cat from the section being cleaned and allow them to be safely housed in the alternate section to avoid contamination from the cleaning and disinfecting chemicals during the cleaning process. The animal caretaker stated that a towel is held up over the portal when the chemicals are sprayed into the enclosure, but this is method is insufficient to safely contain and protect the animals in the enclosure during the cleaning process.

Animals Kept in Filthy Conditions

Hamilton Township Animal Shelter failed to conduct basic cleaning at the shelter. Cats were left to roam over vomited cat food on the window sill, cat furniture, scratching items and under the litter plan. In addition, the cat furniture had an accumulation of fur and litter debris. In other words, when cats rested, exercised and went to the bathroom, they had to expose themselves to old vomit and disease.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.3 (f) There were several areas of vomited cat food in the older section of the facility where the resident cats roam, including on the window sill, carpeted cat furniture, and cardboard scratchers and on the carpet under the cat litter pan. The carpeted cat furniture also contained an accumulation of fur and litter debris. This area, which was previously the main entrance and reception area needed cleaning.

The shelter did not even bother disinfecting the cats’ food and water receptacles on a daily basis. In other words, cats had to consume dirty and likely disease filled food and water.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.7 (e) and (h) Food and water receptacles were not being cleaned and disinfected daily as required. A bird cage located in the previous reception area of the old section of the building contained food, but the animal caretaker stated that the bird had been removed from the facility approximately two weeks prior to this inspection. The animal caretaker stated that the food and water receptacles for cats are washed with a detergent, rinsed, and hand dried, but these receptacles are not disinfected daily.

The shelter may very well have fed animals tainted food. Specifically, the shelter left a bag of dog food open and had a can of cat food that expired three years before in the refrigerator.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.3 (c) Opened bags of food were not stored in sealed containers to prevent contamination or infestation. A large opened bag of dry dog food was found in the room where the ferret was located. An unopened can of kitten food which had expired in 2015 was found in the refrigerator in the isolation room.

After animals left the facility, the shelter failed to clean and disinfect their cages for extended periods of time. How much disease built up and spread while these cages were left filthy?

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.8 (c) The small animal cages were not being cleaned and disinfected for a significant amount of time after an animal is removed from the facility. The bird cage in the older section of the facility had not been cleaned and disinfected since the bird was removed from the premises approximately two weeks prior to this inspection. Ten empty cat cages in the adult cat room and three empty cages in the adoption room contained wood and paper litter debris and fur and had not been cleaned and disinfected the day the animals were removed from the enclosures. The animal caretaker stated that four cats had been adopted on the previous Saturday, but inspectors were unable to determine how long the other nine cages had been empty without being cleaned and disinfected. A wire dog crate that was set on the floor and did not contain a crate tray contained an accumulation of spilled dog kibble, feces, and other debris. This crate was located against the back wall directly adjacent to other crates in this room and needed to be removed from the room to adequately clean and disinfect both the crate and the floor.

If that was not bad enough, the shelter failed to clean and disinfect the cat enclosures they did attempt to clean:

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.8 (c) The cleaning and disinfecting products available at the facility for the cat enclosures were not being used in accordance with the manufacturer’s label instructions and in accordance with these regulations. Enclosures are required to be thoroughly cleaned with a detergent solution, rinsed to remove the dirt, debris and chemical residue from the cleaning process, followed by the application of a safe and effective disinfectant.

Shelter staff used Mr. Clean, which apparently wasn’t very “clean”, given it had “an opaque precipitate or growth floating in the liquid.” When asked, the employee couldn’t even say what this gross substance was in the bottle. Furthermore, the shelter did not even create fresh bleach cleaning solutions each day and did not use the right amount of the bleach in the solutions. In fact, the shelter lacked even a measuring device to mix bleach and water to the proper concentration. Based on the shelter worker’s recollection, the shelter used a bleach solution that was 7-10 times greater than the required concentration. Thus, the shelter likely exposed cats to harsh bleach concentrations that could have possibly irritated the animals’ skin and lungs.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.8 (c) Inspectors found a spray bottle in the cat adoption room with a Mr. Clean label that contained a clear liquid with an opaque precipitate or growth floating in the liquid. An animal caretaker told inspectors that the bottle contained bleach but was unable to determine when it was mixed or what the contamination was floating in the bottle. Bleach solutions were not made fresh daily as required and the bottles used to mix cleaning and disinfecting solutions were not marked with the contents and ratio of mixed use solution and the date the solution was prepared. There were no measuring devices available on the premises to accurately measure the disinfecting bleach and water or other chemicals as required. Inspectors were told that water and bleach was poured into containers without being measured. When an animal caretaker was asked what ratio of water to bleach was used, inspectors were told three parts water to one part bleach (1:3), which is approximately 7 to 10 times higher than the mixed use concentration specified on the manufacture’s label for disinfecting bleach, depending on the percentage of sodium hypochlorite in the product and the target organism.

Even when the shelter put Mr. Clean down in the cat intake room, it failed to subsequently put a disinfectant down to kill pathogens. But don’t worry, the shelter had a bottle of disinfecting bleach in this area that it did not use!

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.8 (c) The animal caretaker stated that the cat enclosures in the intake room were sprayed down with Mr. Clean, allowed to set approximately 5 minutes to loosen the debris and wiped down before clean bedding and litter was placed into the enclosures. This cleaning step was not being followed with the application of a disinfecting solution followed by the required set time, which is usually 10 minutes depending on the product used and mixed-use ratio, to allow for adequate disinfection of the precleaned surfaces. A bottle of disinfecting bleach was found in the cat intake room, but the animal caretaker stated that it was not being used on the day of this inspection.

Building Fails to Comply with State Law Despite $1.1 Million Renovation

The shelter’s “new” section had floors with a material or coating that was not impervious to moisture. Furthermore, older sections of the facility had broken floor tiles that made the surfaces not impervious to moisture. Similarly, the indoor and outdoor dog enclosures had peeling paint making those surfaces not impervious to moisture. Thus, the shelter couldn’t clean and disinfect these areas properly even if it had correct cleaning procedures.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.4 (f) The inspectors were told that the floors of the new section of the facility were unable to be disinfected because of the material or coating on these floors. The floors were not constructed so that they may be readily cleaned and disinfected as required. The floors of the older section of the facility contained broken floor tiles in some areas and therefore, were not impervious to moisture and able to be readily cleaned and disinfected. Carpeted cat furniture used for the resident cats at the facility cannot be sufficiently cleaned and disinfected. The indoor dog enclosures in the older section of the facility had peeling paint and these surfaces were no longer impervious to moisture and able to be readily cleaned.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.5 (e) Surfaces of the outdoor enclosures in the older section of the facility had peeling paint and were not maintained so that they were impervious to moisture and were unable to be readily cleaned and disinfected.

Once animals inevitably got sick in this cesspool of disease, the shelter could not even properly isolate sick animals from healthy ones in the facility. Specifically, even after spending $1.1 million on a shelter renovation project, the facility lacked functioning and legally required isolation areas. Thus, sick animals likely spread their diseases to healthy animals.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.9 (g) The facility does not have an isolation room to house dogs with signs of communicable disease.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.9 (h) Inspectors were told that the isolation room for cats does not have an exhaust system which creates air movement from the isolation room to an area outside the premises of the facility. The HVAC system is not separated and the exhaust air from the isolation room is permitted to enter or mix with fresh air for use by the general animal population.

Shelter Fails to Provide Proper Veterinary Care

Hamilton Township Animal Shelter failed to have its supervising veterinarian establish a written and adequate disease control program. In fact, the shelter could not provide any evidence that this veterinarian had visited the facility let alone provided any care. In other words, the very veterinarian who defended the shelter in Mayor Yaede’s press release, failed miserably at his job servicing the shelter’s animals.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.9 (a) The supervising veterinarian had not established a written disease control and adequate health care program at the facility and a disease control program was not being sufficiently maintained under the supervision of the veterinarian. Inspectors were told that animals are taken to three area veterinary hospitals when care is needed, and the supervising veterinarian visits the facility periodically, but there was no evidence or documentation indicating when the veterinarian had visited the facility and what care, if any, had been provided to animals at the facility. There were no veterinary medical records, veterinary treatment orders, medication administration logs or other documents available on the premises for animals that had received veterinary care from area veterinary hospitals. The veterinary hospital documents were said to be released to the adopter when the animal left the facility. Veterinary treatment documents were not kept on file for animals that had been euthanized at the facility.

The shelter’s 2018 disease control program form that must be signed by the supervising veterinarian was effectively a fake document. Specifically, the 2018 form was a photographed copy of the 2017 form with the veterinarian’s name and license number changed. The signature on this form did not match the veterinarian’s signature on the policy and procedure document stating the shelter takes sick animals to the veterinarian. Finally, the shelter’s license number listed on the 2018 form was the 2017 license number even though a 2018 shelter license number was never issued. If shelter management pulls these shenanigans with publicly accessible paperwork, can we really trust them to treat animals properly behind closed doors?

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.9 (b) The facility did not have a VPH-20 form signed by the supervising veterinarian for the current year indicating that a disease control and health care program is in effect at the facility. The VPH-20 form posted at the facility and dated 1/2/18 was a photocopy of the signed form dated 1/3/2017 with the date and the veterinarian’s name and veterinarian’s license number changed. The photocopied signature on the VPH-20 form did not match the signature on a policy and procedure document that stated animals with signs of illness or wounds of unknown origin are taken to a veterinarian. The veterinarian’s name was changed on both documents. Although the facility was not issued a license number when a license was issued for 2018, the photocopied VPH-20 document shows the facility license number as 090, which was the photocopied information from a previous year.

Hamilton Township Animal Shelter killed many animals citing medical conditions without having any records to indicate the facility provided any veterinary care.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.9 (a) Numerous animals were recorded in the disposition logs and/or the euthanasia logs as “sick,” “very sick,” “URI,” “emaciated,” etc., but no veterinary medical records were available to indicate that these animals had received treatment before being euthanized or transferred. Examples included, but were not limited to: C538, euthanized 12/30/16, “very sick, URI since 11/28/16”; C533, C534, C535, and C536, euthanized 12/6/16, “very sick, trapped”; C546, transferred 1/12/17, “URI”; C547, died at shelter 12/9/16, “very old”; C545, euthanized 12/5/17, “very sickly”; C417, C418, C420, C421, C422, euthanized 9/22/17, “URI emaciated” (#419 died at shelter); C3, euthanized 1/18/18, “flat ear, very sickly”; C10, euthanized 1/21/18, “very sickly”; and 46 cats from a hoarding house were documented as euthanized on the same day of intake due to “medical issues.”

The shelter also had numerous expired medicines with no records indicating whether the shelter gave these drugs to animals. If the shelter did in fact give expired medicines to animals, they put the animals health at risk.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.9 (a) There were numerous bottles of expired medications that had been prescribed by various animal hospitals to animals that had been housed at the facility, but there were no medication administration logs or other treatment records available to indicate why these medications had not been administered as prescribed on the prescription labels. Examples of medications included, but were not limited to: buprenorphine, expired in 2015; cephalexin, expired in 2013, and another dispensed in 2015, expired; clindamycin, dispensed in 2015, expired in 2017; Rimadyl, expired in 2017; two full bottles of expired amoxicillin-clavulanate, one prescribed to Haley and one to Connie; clindamycin prescribed to Onyx on 4/30/17, not administered; 3 boxes of Meloxidyl for cats, dispensed 8/15/15, expired in 2017; Deramaxx, expired 5/17; and a full bottle of Rimadyl prescribed to Sparky 5/2016, expired 2017.

A dog that was currently at the facility at the time of this inspection was prescribed cephalexin on 10/13/15 (20 caps) which had since expired. This bottle was full but there was no documentation available to indicate why this medication had not been administered as prescribed.

Dog number 116, described as a Rottweiler mix, was dispensed enrofloxacin on 12/13/17, but this bottle of 30 tablets was full and had not been administered as prescribed. This same dog was also prescribed 14 caplets of Novox on the same date, 12 of which remained in the bottle and were not administered as prescribed.

Inhumane Killing Methods

Hamilton Township Animal Shelter primarily used intracardiac injections, otherwise known as heart sticking, as the “primary method” to kill animals instead of the recommended intravenous method. As the name implies, heart sticking involves stabbing an animal in the heart and injecting poison. Under state law, heart sticking can only be used when an animal is heavily sedated or comatose with a depressed vascular function. Why? The killing method is so brutal that an animal must be completely unconscious and “have no blink or toe-pinch reflexes” according to the Humane Society of the United Stated Euthanasia Reference Manual.

If that was not bad enough, the shelter used the wrong euthanasia drug to kill cats. Specifically, the euthanasia drug Hamilton Township Animal Shelter used is only approved for dogs. Given the drug the shelter uses, sodium pentobarbital combined with phenytoin sodium, can lead to cardiac arrest before the animal goes unconscious in certain circumstances, this is deeply concerning.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.11 (c) The method of injection that was being used for euthanasia of cats at the facility was not acceptable as the primary method of injection of the euthanasia solution. The primary method of euthanasia for cats was said to be an intracardiac injection of a euthanasia solution. The recommended method is an intravenous injection of a barbiturate. Intracardiac and intraperitoneal injection may be made where intravenous injection is impractical, as in the very small animal, or in the comatose animal with depressed vascular function. The product being used at the facility contains pentobarbital sodium and phenytoin sodium and is licensed for use in dogs only. The package literature for this product states that it is approved only for IV and IC injections in dogs (not to be used in other body cavities due to the addition of phenytoin sodium in the product).

More disturbing, the shelter did not even weigh animals before killing them. Instead, the shelter used weights from the time the animal came into the shelter to determine the dose of tranquilizing agents and poison used to kill animals. Since the facility had no working scale, one must question if the shelter actually weighed the animals when they arrived. Even if staff weighed animals upon intake, an animal may lose or gain weight once at the shelter. Therefore, there is a good chance the animals were given the wrong drug dosages.

If animals were given too low a dose of euthanasia drugs, the shelter may have disposed of animals, such as in a landfill or in a crematorium, while they were still alive. In other words, animals could have been buried and burnt alive. Similarly, if animals were not given enough sedatives, the animals may have experienced significant pain when killed. This is especially the case since the shelter used the barbaric heart stick method to kill pets.

The shelter’s own records did indicate some animals were given too little euthanasia drugs. Furthermore, the shelter’s euthanasia logs contained numerous errors and raise questions as to whether the shelter killed even more animals inhumanely.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.11 (f) Written instructions were not posted in the euthanasia area and there were no instructions available that included the dosages by weight in pounds of all euthanasia, immobilizing, and tranquilizing agents used at the facility. Animals were not being weighed prior to administration of euthanasia, immobilizing, or tranquilizing agents. A scale was unavailable at the facility to weigh dogs and the scale for small animals was inoperable at the time of the inspection. The weight recorded on an animal’s record at the time of intake was being used to calculate the dosages of these agents, but the weight on intake may not be the same weight of the animal at the time it is euthanized. It was unclear how the weight of each animal was obtained on intake when the facility did not have any working scales to weigh animals.

The weight of animals recorded in the euthanasia logs compared to disposition logs did not match, which indicated that the dosage by weight for several animals may have been miscalculated. Some examples of errors included but were not limited to the following: Dog number 16, released to the facility by its owner on 1/30/17 was recorded in the disposition log with a weight of 120 lb., but the euthanasia log shows the weight of the dog as 80 lb. This dog was administered 10 mL of euthanasia solution rather than the minimum 12 mL required for a 120 lb. dog. Dog number 17, released by its owner on 1/30/17 was record in the disposition log with a weight of 65 lb. This dog was listed as 80 lb. on the euthanasia log on 1/31/17 with a dosage of 10 mL recorded on the euthanasia log and 9 mL recorded in the disposition log, both of which are suitable for either of these recorded weights depending on the route of injection. Dog number 31 which was released to the facility by its owner on 2/22/17 and euthanized the same day was recorded in both the disposition log and the euthanasia log with a weight of 12 lb., but both records indicate that this dog was only administered 1 mL of euthanasia solution, which is suitable for a 10 lb. dog depending on the route of injection. Dog number 19, recorded in the disposition log with a weight of 80 lb. was euthanized on 2/11/17, but was not recorded on the euthanasia log. The disposition records indicate that this dog was administered 4 mL of euthanasia solution, but the tranquilizing agent is recorded as “8”, so it is possible these numbers were written in the wrong column and the dog may have been given 8 mL of euthanasia solution which is suitable for an 80 lb. dog depending on the route of injection. Dog number 239, recorded as a 75 lb. Labrador in the disposition records but recorded as 30 lb. in the euthanasia log on 9/4/17, appears that it should be dog number 240. Dog number 198 recorded in the euthanasia log on 10/24/17, appears that it should be dog number 298, but dog number 198, euthanized on 8/1/17 according to the disposition log, is missing from the euthanasia log.

State health department inspectors noted the shelter likely guessed the weights of wildlife when it used euthanasia drugs to kill these animals. Even worse, the inspectors mentioned the weights of several animals were probably not accurate indicating the shelter may have inhumanely killed these animals as well.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.11 (f) The weights recorded in the euthanasia records for various species of wildlife appear to be rough estimates due to the descriptions provided. The estimated weights and the calculated dosages recorded for some wildlife species, such as the injured rabbit on 4/21/17 and the injured squirrel on 4/22/17 do not appear to be accurate and the dosages of euthanasia solution administered may be insufficient. The supervising veterinarian should include the dosages by weight for various wildlife species when developing the instruction sheets for animal euthanasia.

If this was not bad enough, the shelter appeared to incorrectly use sedatives to comfort animals while they were killed with a stab to the heart. The shelter had no dosage instructions or logs of the tranquilizers it used. In other words, the shelter could not prove it knew how to provide sedatives to animals and if it even did. Furthermore, the tranquilizing agents mixed with sterile water at the facility were not refrigerated giving them a useful life of just seven days. The shelter did not put dates on these sedative solutions and it seems likely the shelter could have used such solutions after their seven day shelf life. Thus, the shelter may have provided animals ineffective sedatives if the facility actually used tranquilizing agents at all.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.11 (f) There were no prescription labels, instructions for use, dosage calculation sheets, or substance usage logs for the anesthetic agent used at the facility. There were several bottles of this agent found on the premises, and the inspectors were told that these bottles were ordered by the local health department through the supervising veterinarian, but no records were available to indicate that this product was being used by or on the order of a licensed veterinarian. The manufacturer’s package insert for this product indicates that this product is to be reconstituted with 5 mL sterile water, but there were no bottles of sterile water found with this anesthetic agent. The package insert states to discard unused solution after 7 days when stored at room temperature or after 56 days when kept refrigerated. The reconstituted product was not stored under refrigeration and there was no date marked on the bottle or records available to indicate when the bottle had been reconstituted.

Shelter Employees Not Trained to Perform Humane Euthanasia

Several employees “euthanizing” animals at the shelter did not have legally required certifications by a licensed veterinarian. Given the horrific killing practices noted above, is it a surprise the staff did not receive the mandated training?

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.11 (e) Two employees administering animal euthanasia at the facility were not certified by a licensed veterinarian in the acceptable euthanasia techniques used at the facility. Inspectors were told that these two employees had taken a 16-hour “Euthanasia by Injection” course which was based on the Humane Society of the United States’ Euthanasia Reference Manual and was offered by a humane organization in Pennsylvania on February 26 and 27, 2015, but this course is not approved to replace the direct supervision, training and certification by a licensed veterinarian in the State of New Jersey. The trainer listed on the course document was not a licensed veterinarian and inspectors were told that no hands-on training was provided.

Another employee who was certified by a licensed veterinarian to perform euthanasia, was not sufficiently trained in the acceptable techniques; specifically, IV injection as the primary method of euthanasia for cats. Additional training and certification in administration of IP injection will also be required if this technique will be used at the facility.

Shelter Drug Records Raise Concerns About Where Controlled Substances Went

Inspectors found the shelter failed to include 67 milliliters of euthanasia drugs in the usage logs provided to the state’s Drug Control Unit. Furthermore, the shelter did not even keep usage records for sedatives it used. Given these are controlled substances, major questions arise as to whether the unaccounted for drugs are due to incompetent shelter management or people using these substances for nefarious and illegal purposes.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.11 (f) Many animals that had been euthanized at the facility were not recorded on the euthanasia substance usage logs as required under the authority of the New Jersey Department of Law and Public Safety, Division of Consumer Affairs, Drug Control Unit. Records indicated that at least twenty animals were recorded in the disposition logs as euthanized during the year 2017, but these animals were not recorded on the pentobarbital sodium usage log forms, resulting in approximately 67 mL of euthanasia solution unaccounted for. Approximately 200 records on the euthanasia log forms and over 150 records on the disposition record logs were missing the name or initials of the certified personnel who had administered euthanasia and tranquilizing or anesthetizing agents to these animals.

There were no prescription labels, instructions for use, dosage calculation sheets, or substance usage logs for the anesthetic agent used at the facility.

Shelter May Have Killed More Animals Inhumanely

Hamilton Township Animal Shelter failed to keep proper intake and disposition records. Shelters are required by law to keep specific details on each individual animal, such when it came in and left and its outcome. Inspectors noted many animals had different information in their intake and disposition records and the euthanasia logs. Therefore, its quite possible Hamilton Township Animal Shelter’s reported statistics are wrong.

Furthermore, the shelter did not document how it killed animals as required by state law.

N.J.A.C. 8.23A-1.13 (a) The method of euthanasia, such as IV, IC, or IP, was not recorded in each animal’s record as required or on any other document maintained at the facility. There were numerous errors found in the intake and disposition log records and the euthanasia log records including but not limited to the following examples: Two cats were given the same ID number 110, one on 5/3/17 and another on 5/4/17; dog number 310 was recorded as euthanized on 11/25/17, but was also recorded as reclaimed on 11/14/17; cat number 502 (2016) was recorded as adopted on 3/15/17, but was also recorded as euthanized on 9/1/17 with a notation “URI 8 months”; cat number 372 was recorded as euthanized on 8/24/17, but was also recorded as adopted on 10/4/17; cat number 111 was recorded as euthanized on 5/9/17, and was recorded as euthanized again on 8/24/17; there was no ID number for a cat euthanized on 2/23/17; cat number 579 that was euthanized on 1/7/18 was not recorded in the disposition log and cat number 581 that was euthanized on 1/7/18 was not recorded on the euthanasia log. These types of errors can result in discrepancies in the amount of euthanasia solution used and recorded on the New Jersey Drug Control Unit’s Sodium Pentobarbital Usage Log Forms.

Employees responsible for filling out intake records need to take care to accurately describe the animal and its distinguishing marks. If the breed of dog cannot be easily determined, the animal may be described by hair length, coat type, weight and build. It was recommended to obtain a breed chart for dogs to assist in selecting the closest breed, but to avoid significant errors, such as describing a Havanese type mixed breed as a chihuahua, the breed of dog may be recorded as mixed with an accurate description of its characteristics.

Mayor Yaede’s Monumentally Poor Response

Hamilton’s mayor responded hours after the inspection report’s release declaring “State inspection report does not list one finding of animal abuse or animal cruelty” and “the majority of the report cited clerical errors and other items that have already been corrected.” First, the New Jersey Department of Health does not bring animal cruelty charges. However, the report did in fact document numerous potential examples of animal cruelty. It is up to law enforcement authorities to bring charges. Specifically, law enforcement authorities could bring charges for killing animals before seven days, not providing veterinary care, leaving animals in dangerous conditions and killing animals inhumanely. In addition, law enforcement officials should bring individual charges for every single animal that endured these atrocities. As this blog details, these are far more than a few “clerical errors.” Finally, based on past experience, I find it next to impossible to believe this shelter fixed all of the extensive problems, particularly those involving the actual structure of the facility.

Mayor Yaede also falsely claimed the state health department’s “recommended method of euthanasia”…”appears not to be a State requirement.” In fact, N.J.AC. 8.23A-1.11 (c) (1) states IV injections are the preferred method and heart sticking is only allowed on a heavily sedated or comatose animal with depressed vascular function. Furthermore, the shelter failed to weigh animals, at least properly, per the inspection report, which also is required by state law to ensure humane euthanasia.

The good mayor also claimed the fact the shelter remained open proved all was fine. The state health department almost never shuts a shelter down. Even after the most egregious state inspection reports, the New Jersey Department of Health has never in recent years shut a shelter down after an initial inspection. Simply put, the state health department does not do so since it fears the repercussions of where the displaced animals will go. In other words, saying your shelter isn’t so bad because it wasn’t immediately shut down is about as a low standard once can try to achieve.

Mayor Yaede then tried to claim all the killed animals at the shelter were mercy killings where owners requested euthanasia. As the state report found, stray animals were also illegally killed before seven days passed. Therefore, those animals were not owner requested euthanasia. Additionally, 46 cats were immediately killed illegally on a single day last year and the records indicated most were treatable (i.e. URI, ringworm, etc.). Furthermore, true owner-requested euthanasia, where a shelter humanely ends the life of a hopelessly suffering animal, makes up a very small percentage of an animal control shelter’s total animal intake. For example, owner requested euthanasia only made up 0.7% of the total dogs and cats Kansas City Missouri’s animal control shelter took in during 2017. While Hamilton Township Animal Shelter or any other facility can claim many of the animals it killed were “owner requested”, that does not mean the animals were hopelessly suffering.

What was the other mayor’s other excuse? The state health department inspected on a “Monday morning during the very same time when routine cleaning operations would normally occur following the weekend.” As regular readers know, this is a typical and nonsensical excuse used by regressive shelters. Good shelters don’t allow their animals to live in filth period. Even more troubling, Mayor Yaede’s statement suggests the shelter is NOT cleaned during the weekend. If that is the case, the shelter has even bigger problems than we thought.

Mayor Yaede then goes on to claim Hamilton Township’s Council members are mean to call the shelter staff “killers.” After reading this report and the shelter’s 2017 Shelter/Pound Annual Report, we know the shelter leadership are “killers” since they illegally and quickly killed animals despite the facility having empty cages. Simply put, shelter management would rather kill animals than do the work caring for them.

Finally, Mayor Yaede stated she “worked tirelessly to help promote the adoption of our shelter animals” and is a “forceful advocate for our animal shelter and our shelter’s pets.” If she was “working so tirelessly” and such a “forceful advocate for our animal shelter and our shelter’s pets”, she wouldn’t have circumvented the town’s ban on pet store puppy sales by buying a puppy from a nearby community’s pet store. The mayor should call herself a puppy mill princess instead.

As I previously stated, Hamilton residents must demand serious reforms at the Hamilton Township Animal Shelter. Specifically, they must accept nothing less than the following:

- Fire shelter manager Todd Bencivengo and other key employees and replace them with a competent and compassionate shelter manager and staff members who will save lives

- Create a No Kill Implementation plan similar to the one in Austin, Texas that mandates the shelter fully put the No Kill Equation into place and achieve a minimum 90% live release rate

However, after seeing Mayor Yaede’s and her Health Officer’s reactions to this inspection report, I believe the town would be better off with EASEL Animal Rescue League operating the shelter. Given EASEL Animal Rescue League receives less than half the taxpayer funding per impounded animal than Hamilton Township Animal Shelter and achieves very high live release rates, both Hamilton’s animals and taxpayers would benefit from this organization running the Hamilton Township Animal Shelter.