12/2/16 Update: Subsequent to my publishing of this blog, the borough of Teterboro sent me a second inspection report. This report, like the other, indicated the Bergen County Health Department failed to properly inspect the shelter it runs.

12/27/16 Update: The borough of Teterboro provided me the 2016 inspection report after I posted this blog. As with the 2014 and 2015 inspection reports, this inspection failed to identify the problems discussed in this blog.

In Part 1 of this series of blogs, I showed how Bergen County Animal Shelter’s statistics prove the county’s claims of running a no kill facility are false. My second blog highlighted the absurd justifications Bergen County Animal Shelter uses to kill many animals. This final blog will explain why Bergen County Animal Shelter kills so many healthy and treatable animals.

Regressive Health Department Controls Shelter

Bergen County delegates control of the shelter to an agency focused on protecting people from animals rather than a department focused on saving lives. Per Bergen County Animal Shelter’s policies and procedures manual, the County’s Health Officer, who is under the authority of the Bergen County Board of Health, is “responsible for the overall operations of the animal shelter” and “sets the policies and procedures of the animal shelter.” The Health Officer, Nancy Mangieri, who has worked as a nurse and in the field of public health diseases, has no apparent expertise in animal sheltering policies on her Linkedin profile.

Health departments typically are terrible at running animal shelters. Given the mission of these agencies are to protect public health, they are often hostile to shelter animals. Theoretically, shelter animals pose a public health risk in that they could have certain diseases or bite someone. Of course, these risks are tiny and the general public would gladly take on these very small risks in exchange for saving lives. That is why shelters have adoption programs after legal hold periods end. However, health departments in my experience are often solely focused on miniscule health risks and seek to eliminate them at the expense of killing healthy and treatable animals. Thus, Bergen County’s elected officials chose to deceive the public about how its overly aggressive Board of Health is killing massive numbers of healthy and treatable animals.

Local health departments typically fail to properly inspect animal shelters. Under New Jersey animal shelter law, local health departments must inspect animal shelters each year. In reality these entities are ill-equipped to inspect animal shelters. Local health departments are used to inspecting places, such as restaurants, which are far different than animal shelters. Furthermore, the same health department that inspects Bergen County Animal Shelter is also responsible for running the shelter. Clearly, this is a conflict of interest and recent experience in the state shows it plays out in poor quality inspections.

Bergen County Department of Health Services’ inspection quality was poor. Upon requesting several inspection reports, the Bergen County Department of Health Services claimed it possessed none of its own reports. Instead, I was instructed to contact the borough of Teterboro, which is where the shelter is located. The 2014 inspection report Teterboro sent me contained literally 10 sentences. The inspection report did not address any of the issues, such as the shelter killing animals during the 7 day hold period and not weighing animals prior to euthanasia, I identified in my last blog. Similarly, the 2015 inspection report had only 3 general sentences. While the 2016 inspection report did point out some issues, the commentary was light and the report still gave the shelter a satisfactory grade. Clearly, the Bergen County Department of Health Services did a poor job of inspecting the shelter it runs.

The Shelter Director, Deborah Yankow, is responsible for carrying out the facility’s policies according the shelter’s policies and procedures manual. Based on Ms. Yankow’s Linkedin profile, she did not seem to have any significant animal shelter or rescue experience prior to becoming the Shelter Director. Furthermore, her Linkedin profile does not seem to show any super successful experience in another challenging field, such as business, law, finance, or medicine, that would translate into her becoming a successful shelter director.

Owner Surrender Policy Proves Shelter Violates 7 Day Hold Period

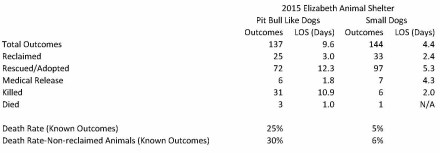

In Part 2 of this blog, I revealed that Bergen County Animal Shelter killed a large number of dogs and cats surrendered by their owners during the 7 day hold period. Bergen County Animal Shelter killed 185 dogs and 210 cats surrendered by their owners. 56% of these dogs and 29% of these cats were classified as owner-requested euthanasia. As discussed in Part 2 of this series of blogs, shelters cannot kill owner surrendered animals under state law during the 7 day hold period unless a veterinarian clearly documents the animal is hopelessly suffering and the veterinarian euthanizes the animal. Based on many records I reviewed, the shelter often did not fulfill these requirements.

Bergen County Animal Shelter’s policy and procedures manual clearly states the facility can kill owner surrendered animals immediately:

Animals in the shelter fall under one of the following categories, which should be clearly defined on their cage cards:

- Owner release: Immediately becoming property of BCAS (available for adoption, rescue, or euthanasia).

- Stray: Found by Good Sam or Animal Control: These animals must await a 7 day hold prior to becoming property of BCAS.

- SPCA case: These animals are housed at the shelter; they are not up for adoption. If sick, the veterinarian on duty and an SPCA official must be contacted immediately.

- Owner hold: These are usually cases where an owner had gone into the hospital and we are holding the animals until further arrangements can be made. We do not do boarding.

- Court Cases

Furthermore, the Owner Release Agreement the shelter puts in its policies and procedures manual clearly states the facility can immediately kill animals who are “sick, injured or unadoptable.” The shelter can only euthanize sick or injured animals if those creatures are hopelessly suffering as documented by a veterinarian. Furthermore, Bergen County Animal Shelter can never immediately kill an animal just because the shelter claims he or she is “unadoptable.”

To make matters worse, this Owner Release Agreement states family members who contest the surrender cannot get the animal back. In other words, an abusive family member can take another family member’s pet to the shelter and the owner could not prevent the shelter from killing their beloved dog, cat or other animal. One of the key reasons New Jersey passed the owner surrender hold period law several years ago was to prevent abusive family members from doing this very thing. Thus, Bergen County Animal Shelter violates both the letter and the spirit of the owner surrender hold period law.

OWNER RELEASE AGREEMENT

New Jersey law (N.J.A.C. 8:23A) defines owner as, “every person having a right of property in that (dog) and every person who has that (dog) in his or her keeping, and when applied to the proprietorship of any other animal including, but not limited to, a cat, means every person having a right of property in that animal and every person who has that animal in his or her keeping”.

By accepting surrender of this animal, the Bergen County Animal Shelter assumes ownership of said animal, including all rights and privileges attendant with such ownership. Those rights include placing for adoption, spay/neutering, immunizing, treating and/or humanely euthanizing sick, injured or unadoptable animals. Once an animal has been surrendered, it may not be released to family members or others who contest this surrender.

I hereby attest that I am the owner of this animal and have the right to surrender that ownership to the Bergen County Animal Shelter I also attest that there are no other parties that can dispute any right to surrender said ownership.

Surrendering Owner’s Name: _____________________________________________________

Address: ___________________________________________State: ________ Zip: _________

Surrendering Owner’s Phone #: ____________________________________________________

Owner’s Signature: _______________________________________Date:__________________

Signature of Shelter Employee witnessing Owner Signature: _____________________________

Temperament Testing Animals to Death Enshrined as a Policy

In Part 2 of this series of blogs, I documented the shelter’s outrageous use of behavioral evaluations to kill dogs. Sadly, the shelter’s policies and procedures manual codifies condemning animals to death based on tests proven by science as unreliable.

While the shelter states it may take staff and volunteer comments into account, “3 experienced staff members” make the life or decision after they conduct their formal evaluation. If the shelter classifies an animal as “unadoptable”, the shelter’s policy is to kill the animal without providing any rehabilitation. While the policy also states it will make “efforts” to send these animals to rescues, Bergen County Animal Shelter’s own records showed the facility only sent 6 cats and 1 dog to rescues during 2015. The shelter states animals are unadoptable if they exhibit “unmanageable health problems” and “unmanageable anti-social behavior characteristics.” As we saw in my last blog and Part 1 of this series, Bergen County Animal Shelter classifies far too many animals in the unmanageable category by the standards of real no kill shelters and even the deeply flawed Asilomar Accords. Even worse, the shelter classifies animals with “an aggressive bite history toward other animals” as unadoptable. For example, a dog that did not like cats or a cat that did not like dogs would be slated for death at this so-called “no kill shelter” based on this policy. Thus, Bergen County Animal Shelter’s culture of killing is codified in its policies.

The policy and objective of the Shelter is to adopt out as many animals as possible. Incoming animals released by their owner and stray animals that have completed their 7 day hold will be evaluated by a committee of 3 experienced staff members, including the animal behaviorist, as to their appropriateness for adoption. Characteristics to be taken into account are: history (if known), temperament and health. Evaluations will be done in a quiet, screened area of the education room using the BCAS evaluation form. Comments by staff and volunteers who have observed the animal during the holding period may be taken into consideration. Notations are to be made on the individual animal record.

Evaluated animals fall into three categories:

- Adoptable – Adoptable animals are those in reasonably good health with no aggressive bite history, who are positive toward humans, get along with other animals and do not display habits or behaviors that will make it difficult for them to adapt to a home environment.

- Potentially adoptable – Potentially adoptable animals are those with no aggressive bite history, whose health problems are relatively minor, non-communicable and manageable with treatment, and whose behavioral problems may be improved with training, exercise and/or socialization.

- Unadoptable – Unadoptable animals are those with serious unmanageable health problems, or an aggressive bite history toward humans or other animals, or who exhibit unmamageable antisocial behavioral characteristics.

Unadoptable – Animals designated as Unadoptable will be humanely euthanized. Efforts will be made prior to that decision for an approved rescue to pull the animal.

Flawed TNR Policy

Bergen County Animal Shelter received much praise from those in the animal welfare community for actively participating in TNR programs. For example, the shelter helped Kearny TNR activists pass a TNR friendly ordinance and alters cats in the TNR program.

Unfortunately, Bergen County Animal Shelter puts too many restrictions on TNR programs. For example, in a recent news article about an effort to enact TNR in Lyndhurst, the shelter suggested only trained volunteers, who must go through a 2 day training course, should feed cats and those volunteers could only feed cats in designated areas. Policies like these often limit the effectiveness of TNR efforts as trap and kill will be used in other areas where TNR is prohibited. Due to the vacuum effect, unaltered cats will quickly move in where trap and kill is practiced. Furthermore, Bergen County Animal Shelter appears to limit cat colony sizes to 10-20 animals based on language in its policy and procedures manual. This may result in sterilizing too small a percentage of the cat population to reduce the number of cats. In contrast, the Million Cat Challenge, inspired by successful return to field programs in places like Jacksonville, Florida, Albuquerque, New Mexico and San Antonio, Texas, advocates returning sterilized healthy cats back to the locations where they were found even when there is no colony caretaker when shelter killing is the likely alternative. Thus, Bergen County Animal Shelter’s advocacy for TNR, which is definitely a good thing, has some serious problems.

Bergen County Animal Shelter’s policy and procedures manual spreads myths about feral cats and the shelter kills feral cats on the behalf of regressive municipalities. Specifically, the policies and procedures manual states cats in unregulated colonies are “likely in poor health”, can become “aggressive when cornered” and “increase the possibility of rabies transmission to humans.” In reality, we know many cats, such as those in the return to field programs described above, are healthy outside of “managed colonies” and do not pose any meaningful health risk to people. Finally, Bergen County Animal Shelter enables regressive municipalities by trapping and killing their so called feral cats. If Bergen County Animal Shelter refused to do this dirty work, many of these municipalities would reconsider their catch and kill statutes.

They tend to congregate in groups or colonies and are usually fearful of and avoid humans, possibly becoming aggressive when cornered. Since their diets and living conditions are unpredictable, they are likely to be in poor health and have generally neither been neutered or immunized. Feral cats often end up salvaging for food in the local dumpster along with wildlife that may be infected with rabies. The proximity of unregulated feral cat habitats to humans increases the possibility of rabies transmission to humans.

In some communities, feral cats are valued for their rodent control activities. Regulated Feral Cat colonies consisting of 10 to 20 cats have been established in those communities with a resident assuming the role of Colony Manager. With the Manager’s cooperation, Bergen County Animal Control Officers trap these animals, have them immunized against rabies and have them spayed or neutered by special arrangement with a local veterinarian. These animals are placed in cages clearly marked T & R (for Trap and Release), are given temporary housing until immunized, neutered, earmarked and returned to the colony.

Other communities have passed ordinances restricting establishments of colonies. Stray cats picked up from these communities generally end up being euthanized since there is nowhere to return them. All incoming stray cats not belonging to the trap and release program are held for 7 days to make sure that they are feral and no someone’s missing pet. Cats and kittens initially brought in as feral may be reassessed as adoptable during the 7 day hold and moved into the general population.

Shelter Makes it Difficult for Pet Owners to Reclaim their Lost Family Members

Bergen County Animal Shelter refuses to provide any information over the phone about animals to owners of lost pets. The shelter’s bizarre policy only allows staff to give a “yes” answer if someone provides a description of the animal. In the past, Bergen County Animal Shelter used to post photos of lost animals and descriptions of where animal control picked them up. Unfortunately, the shelter stopped doing this several years ago and now states that staff on the phone won’t look for your lost pet and you will have to come to the shelter yourself to do so. Clearly, this policy makes it more difficult for owners to find their lost family members and likely results in the shelter killing more animals as well as incurring increased costs as animals needlessly stay at the shelter longer.

Even worse, the shelter charges reclaim fees of $55, $80 and $105 for owners losing their animals for the first, second and third times plus a daily boarding fee. No documented policy I saw allows staff to waive or reduce these fees in cases of hardship. For economically disadvantaged pet owners, the shelter could literally kill their family members if the pet owners do not make these ransom payments.

The Wisconsin Watchdog blog posted a “how to” guide for shelters to increase their return to owner rates. Tips include immediately posting stray dog photos to shelter web sites and Facebook pages (Lost and Found Pets New Jersey is another great place for shelters in this state). Additionally, Wisconsin Watchdog recommends having specific volunteers check lost pet reports and help owners coming to shelters to find their lost pets. Also, they recommend giving guidance to owners on how to find their lost pet who is not at the shelter. Shelters should read and implement all the recommendations. Thus, Bergen County Animal Shelter’s does not follow best practices to increase owner reclaims and therefore make it more likely lost pets will lose their lives.

Bergen County Animal Shelter also refuses to provide rescues or adopters information over the phone about shelter animals. Obviously, any shelter that refuses to talk to rescues who call the shelter about animals is putting animals at risk. Rescues may have to drive long distances to the shelter and may not make the trip if the facility fails to provide important details on animals. Similarly, adopters may not make the trip if the shelter insists on keeping them in the dark about animals. Simply put, this is terrible customer service that has deadly consequences.

In my humble opinion, Bergen County Animal Shelter would rather not let the public know about animals at the shelter since it doesn’t want people to know about the slaughter going on at this facility. Obviously, telling people about animals who the shelter may kill is bad publicity for a self-proclaimed “no kill” shelter.

Shelter policy on giving out information about shelter animals to public/to rescue groups: We do not give out any information on any of our animals over the phone. Once an animal is turned in, it becomes property of the Bergen County Animal Shelter. If someone is interested in a particular animal, they are welcomed to come in and look at the animals. If someone has lost an animal and they want to know if we have it, they can describe it and we can say yes, we have an animal that fits that description, you will have to come in, complete a lost pet report and walk through the shelter. If someone has turned their animal in and they wish to reclaim it, they need to come in. No information about any specific animal is given over the phone regarding the disposition of any animal at the shelter. We do have a website and Facebook page for the shelter and post pictures of animals eligible for adoption.

Shelter’s Restrictive Adoption Policies Increase Killing and Costs to Taxpayers

Bergen County Animal Shelter’s adoption policies do not follow the guidance from the national animal welfare organizations as well as many no kill groups. HSUS, the ASPCA, and Best Friends all favor open or conversational based adoption processes focused on matching people with the right pet instead of looking for ways to deny people. Best Friends’ Co-founder, Francis Battista, described these regressive policies perfectly

The truth of the matter is that animals are dying in shelters because of outdated and discredited draconian adoption policies that are designed to protect the emotional well-being of the rescuer rather than to ensure a safe future life for a dog or cat.

Bergen County Animal Shelter’s policy requiring adopters to prove they own their homes or that their landlord allows pets puts more animals at risk. The HSUS Adopters Welcome guide cites a 2014 study where landlord checks did not result in fewer returned adoptions. Furthermore, HSUS rightly points out that making people prove home ownership diverts staff time from lifesaving work and turns off adopters who feel the shelter does not trust them.

The shelter’s policy requiring entire families and their existing dogs to meet the dog the family wishes to adopt is counterproductive. The Adopters Welcome Guide from HSUS cites a 2014 study showing dog meet and greets did not increase the chance dogs would get along in the home. Such meet and greets are unreliable since both the dog in the shelter and the family’s existing dog are stressed out inside or near an animal shelter. Furthermore, some people may not want to expose their existing dog to the stress of coming to a shelter. Additionally, these meet and greets take staff time away from work that can save lives. Also, arranging meet and greets and visits with entire families often result in animals staying in the shelter longer and more lives lost if the shelter kills for lack of space. HSUS recommends that shelters only arrange meeting with entire families if the families request these meet and greets. Thus, Bergen County Animal Shelter’s onerous policy requiring meet and greets increases killing and costs to taxpayers.

Finally, Bergen County Animal Shelter’s refusal to adopt animals out as gifts results in more killing and increased costs to taxpayers. The ASPCA has authored peer reviewed research showing animals adopted out as gifts are just as loved and likely to remain in their homes as animals not adopted out as gifts. Similarly, HSUS also recommends shelters adopt out animals as gifts in their Adopters Welcome guide. Clearly, adopting out animals as gifts safely moves more animals out of shelters and reduces taxpayer costs. Thus, Bergen County Animal Shelter’s prohibition on adopting out animals as gifts is wrong, deadly and costly.

Despite all these adoption restrictions, the shelter’s return rate of 8% was about the same rate as the average shelter and actually twice as high as an urban shelter that implemented an open or conversational based adoption policy.

Limited Adoption Hours Increase Length of Stay and Killing

Bergen County Animal Shelter is hardly open for adoptions. The facility is only open to adopters for around 4 hours on most days and does not adopt out animals on Mondays. Additionally, the shelter only adopts out animals to 5:00 pm or 5:30 pm on the other days it does adoptions except for Thursdays. On Thursdays, the shelter adopts animals out until 6:30 pm, but that may still be too early for many working people who must contend with rush-hour traffic in the area. Thus, Bergen County Animal Shelter’s limited adoption hours result in longer lengths of stay and more killing.

Adoption Profiles Paint Dogs in a Terrible Light

Adoption profiles are marketing tools designed to bring people into the shelter to consider adopting. Best Friends advises shelters and rescues to accentuate an animal’s positives. Similarly, the Deputy Animal Services Officer of Austin Animal Center, which is the largest no kill animal control shelter in the country, strongly recommends shelters use adoption profiles to market animals and adoption counseling sessions to disclose all facts about animals and provide guidance on transitioning the dog into a home environment. Specifically, this successful municipal no kill shelter leader states to not put home restrictions in the adoption profile itself. Obviously, writing a negative adoption profile can prevent people from coming to the shelter to adopt. Thus, shelters should use adoption profiles to bring people into the shelter where adopters and shelter staff/volunteers can honestly discuss the animal and determine if the pet is the right fit for the family.

Bergen County Animal Shelter’s dog adoption profiles turn adopters off. The shelter’s dog adoption profiles read very much like the shelter’s overly harsh behavioral evaluations. Basically, they highlight alleged flaws and make them seem like overwhelming problems. Often, the shelter makes it seem like Cesar Milan or Victoria Stillwell could only adopt these dogs.

The shelter’s adoption profile for Fawn illustrates this misguided philosophy. The adoption profile states the following about Fawn:

- She is shy

- Has an unknown history

- Needs a calmer home

- Do not socialize until she forms a bond with the family

- Need to do various things to build her trust

- Was returned to the shelter

- Gets anxious if she feels confined and out of options

- No first time owners

- No children

After reading this profiles, how many potential good homes ruled out Fawn without ever meeting her? While I personally think some of these faults may not be accurate, the shelter should not write such damning adoption profiles as it makes Fawn and shelter animals in general seem like damaged goods.

Bergen County Animal Shelter’s adoption profile for Brooklyn also hurts her chances for adoption. While the shelter took a great photo, the language reads more like a legal disclaimer than a marketing effort. Specifically, the shelter stated the following about Brooklyn:

- She is a special needs adoption

- She needs a very experienced home

- Needs an adult only home that has experience with dog behavior issues

- Needs a home with no other pets and kids

Speaking as someone who adopted a dog with a similar label as Brooklyn, I have to think how my family could not adopt her. We are not an adult only home and therefore would be rejected. Furthermore, we’ve fostered numerous dogs (who all got along good to great with our dog who had the same label as Brooklyn) that would also disqualify us from adopting Brooklyn. After posting this profile, the shelter basically ruled out hundreds or even thousands of homes without ever talking with these people. Thus, Brooklyn, who has been at the shelter since April 27, 2015, has stayed at the facility way longer than she should have.

Bergen County Animal Shelter’s adoption profile for Captain America also made it harder for him to find a good home. The profile states the following:

- He is not polite

- People will need to have lots of time to train and exercise him

- He is not properly socialized

- He will mess up your house

- Adult homes (17 years old plus) only can adopt him

Clearly, this adoption profile would eliminate most potential good homes for Captain America for his main crime of being a big puppy. In fact, Dr. Emily Weiss of the ASPCA has written that shelters should in fact adopt out dogs like Captain America to families with young children. Significant numbers of shelter dogs fit Captain America’s description and do fine in many homes. Unfortunately, Bergen County Animal Shelter’s awful marketing and insane adoption policies relegate dogs like Captain America to long shelter stays and even death.

Shelter Makes it Difficult for Volunteers to Help Animals

Bergen County Animal Shelter makes volunteers sign a form that may make these kindhearted people think twice about helping animals. The shelter’s volunteer manual includes a form that requires volunteers who work with cats or dogs to sign off on having around 2 dozen “essential” physical, mental and emotional capabilities and other abilities. Some of the “essential capabilities” include

- “Quick reflexes and ability to use both hands simultaneously”

- “Must have the ability to judge an animal’s reaction and to change voice to a soft or strong, authoritative tone in order to calm a dog’s response or give commands”

- “Possess immune system strong enough to tolerate exposures to zoonotic diseases such as ringworm and mange”

- “Ability to cope with unexpected animal behavior without assistance”

While these characteristics are good to have, making volunteers sign off on all these may very well make many good people think twice about volunteering. In other words, its a way for Bergen County Animal Shelter to say it has a volunteer program, but reduce the number of pesky volunteers who could expose the shelter for the fraud that it is. Furthermore, this form is a politically convenient way for a regressive health department to limit the number of people exposed to animals they views as public health risks.

Bergen County Animal Shelter also has very restrictive dog handling protocols that hinder dog socialization and efforts to adopt out these animals. For example, volunteers never can allow, unless they receive permission from the behavioral staff, two dogs to intermingle or go nose to nose within 10 feet of each other. Furthermore, volunteers cannot do meet and greets (i.e. dog introductions) unless they have been trained by the behavioral staff, shadow the behavioral staff or an approved volunteer on at least two meet and greets, “have a very good understanding of canine body language”, and have at least 40 volunteer hours. Clearly, volunteers do not need these inordinate amount of restrictions unless the shelter views all dogs as ticking time bombs. Thus, Bergen County Animal Shelter prevents volunteers from helping dogs as much as these animal loving people could.

Bergen County Animal Shelter’s puts massive roadblocks up for volunteers wishing to simply walk dogs. To walk green coded dogs, which are typically under 35 pounds, have no behavioral issues, and are highly adoptable, volunteers must do a number of things including

- Complete an orientation with the Friends of the County Animal Shelter (FOCAS) group and another orientation with Bergen County Animal Shelter

- Complete 4 “Buddy Hours” with an approved “Buddy”

- Pay dues to FOCAS

- Must brush/groom dogs and practice obedience commands and tricks

In other words, to even walk the easiest of dogs, volunteers have to go through hours of training, pay fees for the privilege to walk dogs, and agree to do obedience training. Thus, the shelter’s overbearing requirements make it difficult for people to volunteer to walk the easiest of dogs.

The shelter makes it even more difficult to volunteer to walk dogs coded blue. These dogs, which are typically 35-50 pounds, have never bitten, are “medium” leash pullers, have “mild to moderate jumping or mouthing problems”, and can include “shy or frightened dogs.” Simply put, these are very common dogs at every shelter that almost any volunteer can handle. However, Bergen County Animal Shelter requires volunteers to do the following things in addition to the green coded dog requirements:

- Must volunteer regularly for at least one month

- Must attend 6 weeks of obedience training classes with a perfect attendance record with a practice dog

- Must pass an evaluation of the volunteer’s abilities, including knowledge of dog training (if they fail, the volunteer may or may not get the chance to go through more training to pass this evaluation)

- Must enforce commands dogs learned

- Must teach dogs commands, tricks, proper leash manners, and manners around people

Thus, the shelter needlessly makes it difficult to walk dogs that almost anyone could safely walk.

Bergen County Animal Shelter makes it extremely tough for volunteers to walk dogs coded yellow. Yellow coded dogs include hard leash pullers, jump/mouthy dogs, high energy animals, dogs who have been at the shelter for several months, extremely shy dogs who might snap if pushed too far, dogs who have minor aggression (i.e. food guarding, problems around other dogs or children) and dogs who have left Level 1, Level 2 or Level 3 bites (dogs who have left Level 3 bites also fall under the next more restrictive category at the shelter). According to Dr. Ian Dunbar’s dog bite scale, these are very minor bites:

- Level 1. Obnoxious or aggressive behavior but no skin-contact by teeth

- Level 2- Skin-contact by teeth but no skin-puncture. However, may be skin nicks (less than one tenth of an inch deep) and slight bleeding caused by forward or lateral movement of teeth against skin, but no vertical punctures.

- Level 3- One to four punctures from a single bite with no puncture deeper than half the length of the dog’s canine teeth. Maybe lacerations in a single direction, caused by victim pulling hand away, owner pulling dog away, or gravity (little dog jumps, bites and drops to floor).

Two of the three bites cause no real physical harm and the third causes only a minor injury. In other words, most of the yellow coded dogs are easily handled by people with the physical strength to handle a hard pulling or energetic dog.

To walk a yellow coded dog, a volunteer must go through the following hurdles in addition to those they did to walk green and blue coded dogs:

- Must volunteer for at least 6 months

- Must have at least 2 hours of behavior instruction during volunteer training classes

- Must train a yellow coded dog and pass an evaluation on their ability to handle the dog and ability to conduct obedience training (if they fail, the volunteer may or may not get the chance to go through more training to pass this evaluation)

- Complete yellow coded dog course homework

- Must keep a log when required of all interactions and training done for each dog and give to trainer once a month

With the possible exception of dogs who have Level 3 bites on their records, these requirements to simply walk a dog are insane. At numerous shelters I volunteered at, I and many other people safely handled many dogs like these with virtually no instructions. Of course, a shelter should train its volunteers and have some restrictions, but these are overkill.

Black Diamonds are the shelter’s most risky category of dogs that certain volunteers can walk. While some of these dogs may have serious behavior issues that do require a very experienced volunteer, some of these dogs can be walked by reasonably competent people. For example, this category includes dogs who have “serious” food guarding issues ,”problems around other dogs”, display “problem fence fighting” behavior, and act “excessively” mouthy, pushy, jumpy and unruly as well as dogs who are “extremely shy or fearful” and “who could snap if pushed too far.” However, this category also includes dogs with predictable behavior problems that respond to training and dogs who have been at the shelter for several months. Basically, these are dogs that were evaluated by the shelter’s trainers and determined to have serious behavior issues that may potentially be fixable. However, as we saw in Part 2, many of the dogs doing worse on these evaluations (i.e. killed by the shelter) were dogs that could easily go to most homes. Therefore, I’m highly suspicious of any dog the shelter claims is such a risk unless it actually has inflicted a very serious bite on someone.

Bergen County Animal Shelter’s requirements to walk dogs labeled as Black Diamonds are nearly impossible for volunteers to meet. To walk a Black Diamond dog, volunteers must meet all the green, blue and yellow coded dog requirements and do the following

- Volunteer at the shelter for at least one year

- Attend all required training classes or regularly keep in touch with the trainer/head shelter staff member

- Must attend 2 hour Black Diamond dog course and complete all homework

- Must have at least 4 hours of experience with a trainer or Supervising Animal Attendant

- Must attend a 7 week course with a Black Diamond coded dog and pass an evaluation on their ability to handle the dog and ability to conduct obedience training (if they fail, the volunteer may or may not get the chance to go through more training to pass this evaluation)

- Must keep a log when required of all interactions and training done for each dog and give to trainer once a month

Thus, Bergen County Animal Shelter makes it virtually impossible to simply walk many dogs who could be safely handled by lots of people and are in most need of socialization, exercise and help.

Bergen County Animal Shelter’s volunteer logs prove that these restrictions hurt the facility’s animals. Recently, I requested 3 weeks of volunteer logs from August 2016. Volunteer hours during this period totaled around 245 hours. If we assume volunteer hours stayed at this rate for the entire year, volunteers would provide 4,247 hours annually to the shelter. As a comparison, volunteers at KC Pet Project, which only took over the Kansas City, Missouri animal control shelter a few years ago, logged 30,681 hours in 2015. Similarly, volunteers at the Nevada Humane Society, which is an animal control shelter, contributed 43,259 hours in 2015. In other words, these two no kill animal control shelters, which serve similar numbers of people as Bergen County Animal Shelter, built volunteer programs that log around 7-10 times more hours than Bergen County Animal Shelter. While volunteers at Bergen County Animal Shelter may have contributed some additional hours outside of the shelter, it would not come close to reducing this huge gap. Thus, Bergen County’s hostile attitude towards volunteers and killing results in fewer volunteers, animals not receiving the help they need, and increased costs to taxpayers.

Perhaps the most telling thing about how the shelter views its volunteers is the fact that it prohibits volunteers from counseling adopters or even showing dogs to adopters unless specific permission is granted by the behavioral staff. If the people who know the dogs the best can’t show dogs to adopters, how does one expect adopters to understand the dogs they will bring home?

Spreading Dangerous Myths About Shelter Dogs and Pit Bulls

The shelter’s volunteer manual also gives away its anti-animals views. Specifically, it states pit bulls require owners who are “MORE responsible than other dog owners” and suggests the breed is more of a liability risk. Sadly, this messaging flies in the face of recent research showing that

- Breed identification in shelters is often unreliable

- All animals should be treated as individuals

Is it any wonder why the shelter killed 4 out of 5 adult pit bulls requiring new homes?

Bergen County Animal Shelter’s volunteer manual also stated large numbers of dogs in shelters are damaged goods. Specifically, the manual states a “good amount of them are here because of behavior issues” and ALL dogs adopted from shelters require “some measure of rehabilitation” in a home. Frankly, this sums up the Bergen County Health Department’s views on shelter dogs perfectly and explains why they kill so many of these homeless pets.

Bergen County Animal Shelter Requires Wholesale Change

Bergen County Animal Shelter is a high kill rather than a no kill shelter. As Part 1 of this series of blogs documented, 33% of dogs, 42% of cats and 50% of pit bulls lost their lives at the Bergen County Animal Shelter in 2015. If we only count animals not reclaimed by their owners, 49% of dogs, 44% of cats, 67% of pit bull like dogs and 83% of pit bull like dogs labeled as “adults” lost their lives at this so-called “no kill” facility. Clearly, these death rates vastly exceed the 10% or lower death rate that is generally accepted to meet no kill status. Thus, Bergen County Animal Shelter operates more like a slaughterhouse than a no kill shelter.

The shelter also failed to comply with the weak Asilomar Accords to determine whether the shelter killed healthy and treatable animals. Part 1 of this series of blogs discussed that a condition is treatable under the Asilomar Accords if a “reasonable and caring pet owner/guardian in the community would provide the treatment necessary to make the animal healthy” or “maintain a satisfactory quality of life.” Based on Bergen County being one of the wealthiest counties in the nation (i.e. pet owners provide lots of care to their animals) and the absurd justifications documented in Part 2 of this series of blogs, Bergen County Animal Shelter clearly killed healthy and treatable animals even by the weak Asilomar Accords standards.

Bergen County Executive, James Tedesco, and the Board of Chosen Freeholders lied to the public when they declared the county shelter a no kill facility. Clearly, these elected county leaders knew that their constituents, who as a whole are highly educated and love animals, want their tax dollars to support a no kill facility. Instead of doing the necessary work to serve Bergen County residents, the elected officials bragged about their shelter being no kill when it was in fact high kill.

Not only was the shelter actually a high kill facility, but it also violated state shelter law. In Part 2, I documented numerous occasions where the shelter illegally killed owner surrendered animals during the 7 day hold period. Also, the shelter failed to keep proper records at times as required by law. Additionally, the shelter’s euthanasia logs listed highly questionable weights that suggested the shelter might not have actually weighed animals prior to euthanasia/killing as required by law. Thus, Bergen County Animal Shelter violated state law.

Bergen County residents should be outraged that their tax dollars support a high kill shelter that conducts illegal activities and their elected leaders tried to deceive their constituents. Frankly, many politicians who defrauded the public to this extent on other issues saw their political careers end quickly. If James Tedesco and the Bergen County Board of Chosen Freeholders are smart, they’d come clean and make wholesale changes at the shelter.

Bergen County needs to overhaul the shelter’s leadership. First, the county should remove the Department of Health Services control over the shelter and have the Shelter Director report directly to the County Executive or his designee. Second, the shelter should hire a successful shelter director or assistant director from a medium to large size no kill animal control shelter. Certainly, Bergen County, which is one of the wealthiest counties in the nation, can afford to pay someone who really knows what they are doing. Additionally, Bergen County is a very attractive location for a shelter director with its close proximity to New York City, its great schools, and its educated and wealthy population. Once the county hires a new Shelter Director who would have the authority to make key decisions under this operating structure, he or she can replace behavior and medical staff that are quick to kill animals.

Bergen County Animal Shelter can and should be highly successful. The facility only took in 7.2 dogs and cats per 1,000 residents in 2015. As a comparison, the Austin, Texas animal control shelter took in 15.6 dogs and cats per 1,000 residents and saved 94% of its dogs and cats in 2015. In August 2016, which is one of the highest intake months of the year, this municipal shelter saved over 98% of the 756 dogs and more than 96% of the 694 cats that left the shelter. Bergen County Animal Shelter also has a larger and more modern facility than many other shelters in the area. Furthermore, the facility is located in a major shopping area with lots of traffic. As a result, Bergen County Animal Shelter can not only become a no kill facility, it can take on more municipalities by safely placing animals more quickly.

Bergen County resident must demand immediate action from James Tedesco and the Board of Chosen Freeholders. Three of the seven Board of Chosen Freeholders’ seats (including incumbents, Maura DeNicola and Thomas J. Sullivan, who approved the fraudulent declaration that Bergen County Animal Shelter is no kill) are up for election this November and voters have an excellent opportunity to make their voices heard about the shelter. Simply put, Bergen County residents must make the Bergen County Animal Shelter no kill con job a key election issue and demand a credible plan to quickly make the facility a real no kill shelter.

The lives of thousands of animals in Bergen County are on the line this November. Let’s make the voices of animal loving residents heard.

Around a year after the illegal killing of Daphne and Rocko and the related uproar, the Elizabeth Law Department put out a statement saying people, including city residents, could not volunteer at the animal shelter.

Around a year after the illegal killing of Daphne and Rocko and the related uproar, the Elizabeth Law Department put out a statement saying people, including city residents, could not volunteer at the animal shelter.

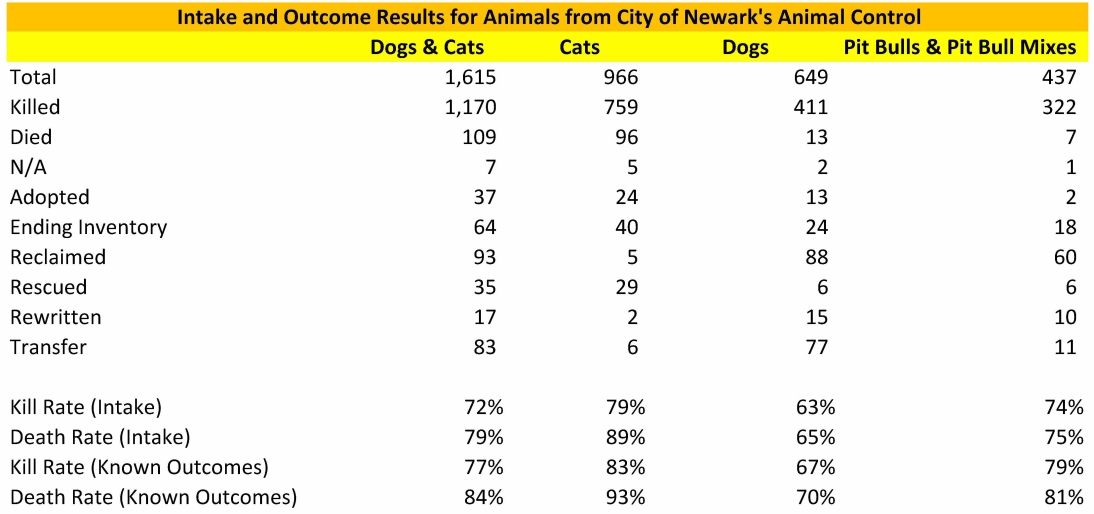

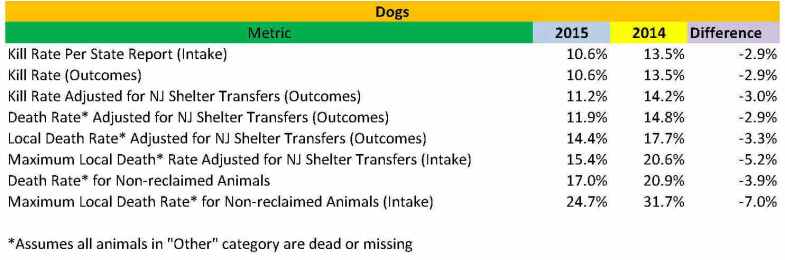

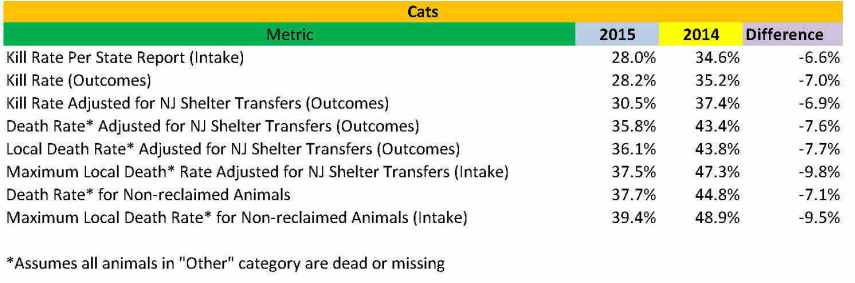

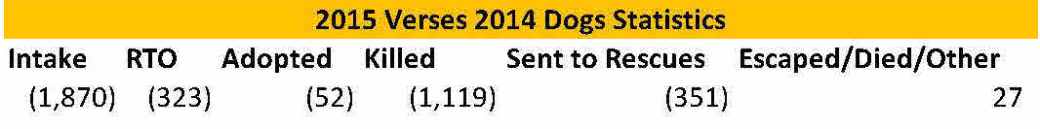

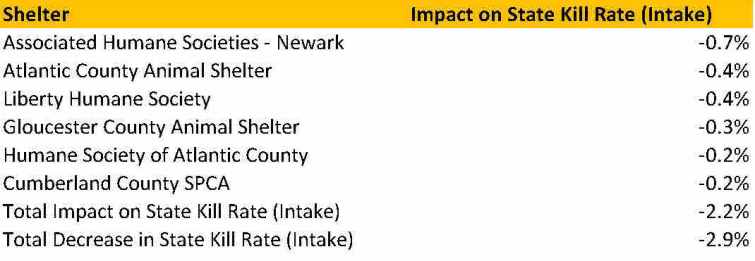

The Animal Intake and Disposition report prepared by the New Jersey Department of Health only allows one to calculate the number of animals killed as a percentage of total animals impounded or intake. I prefer calculating the kill rate as a percentage of outcomes rather than intake as this metric directly compares positive and negative outcomes. Using intake depresses the kill rate since shelters can simply hold animals for a long time to the point of overcrowding. Calculating kill rate based on outcomes rather than intake increases the cat kill rate from 34.6% to 35.2% and the dog kill rate remains the same.

The Animal Intake and Disposition report prepared by the New Jersey Department of Health only allows one to calculate the number of animals killed as a percentage of total animals impounded or intake. I prefer calculating the kill rate as a percentage of outcomes rather than intake as this metric directly compares positive and negative outcomes. Using intake depresses the kill rate since shelters can simply hold animals for a long time to the point of overcrowding. Calculating kill rate based on outcomes rather than intake increases the cat kill rate from 34.6% to 35.2% and the dog kill rate remains the same.